The overwhelming focus of welfare programs in the United States is urban, but the fact that a rural child is more than twice as likely as an urban child to live in the vicinity of persistent high child poverty underscores that any national discussion of child poverty must address the challenges faced by children living in isolated rural areas.

This quote, from a report published by the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire, immediately grabbed my attention when I first came across it in 2016. It squared with the way I felt, as a rural kid from a family that has been rural for generations. It also resonated because at the time I worked for a statewide education grantmaker, Greater Texas Foundation, that maintained a focus on rural students while at the same time concentrating on the more urban areas of the state where most students live. That said, Texas has the largest rural K-12 population in the country—about 600,000—more rural children than some states have kids or even total population.

That quote and report grew into a deeper exploration of rural communities that coincided with my return to living in rural East Texas after 30 years away and with the 2016 presidential election—an individual awakening and what seems to be a national rediscovery of rural issues and concerns. But, rural issues are not really about the election.

We are hearing more and more about rural people and communities these days, but there is no rural monolith. According to Kenneth Johnson, professor of sociology and senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy, “‘Rural America’ is a deceptively simple term for a remarkably diverse collection of places.” Many Americans today no longer have rural ties or connections, and in my conversations over the last couple of years with urban-centric audiences, a picture comes to mind as they describe what they think rural is: a stereotype—unsophisticated, backward, and white.

The reality, though, is that rural America is growing more and more diverse. According to Red Rural, Blue Rural, “Minorities represent 21 percent of the rural population but produced 83 percent of the growth between 2000 and 2010. Hispanics are particularly important to this growing rural diversity… The rural minority child population has grown significantly recently, while the number of non-Hispanic white children diminished.”

In an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data, the Carsey School found that “Black people are nine times more likely to be living in low-income rural counties than in high-income ones.” Carsey researchers also stated, “Poverty is higher in the rural United States, incomes are lower, and job growth is nearly non-existent.”

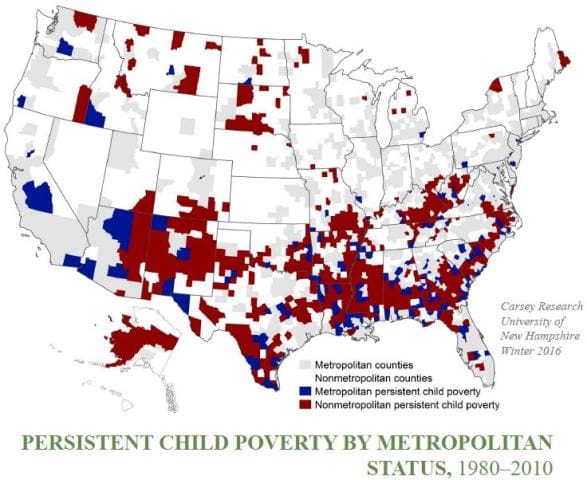

When you put this picture together, what you find is that rural child poverty concentrates across the historic plantation south, in the Ozarks and Appalachia, along the Texas-U.S. border, and on reservations in the midwest and northwest (see the first and third images in the slideshow above). There are three key takeaways from the 2016 Carsey report I led with.

- By 2010, nearly 66 percent of rural counties had high child poverty, compared to just 47 percent of urban counties.

- Only 14 percent of the total child population resides in a rural county, but these counties contain 17 percent of the nation’s poor children.

- About 77 percent of persistent-high-child-poverty counties, which tend to concentrate in rural areas, have a substantial minority child population, compared to just 54 percent of all counties.

With these statistics in mind, private philanthropy needs to take stock of our collective underinvestment in rural America. According to USDA analysis of private foundation grantmaking, only 6-7 percent of private foundation grants benefit rural areas, although 19 percent of the U.S. population lives in rural areas. On the average, rural areas receive less than half the average provided to metro areas (see the second map in the slideshow above). In the Deep South, for example, the Alabama Black Belt and Mississippi Delta receive $41 per capita compared to New York City’s $1,966 per capita.

It is shocking when you put the two maps above side by side. The areas where child poverty concentrates are exactly opposite of where private philanthropy tends to invest (see the first and second maps in the slideshow above). Yes, some private foundations are limited by geography; others are limited by program area; still others by geography and program area. But to the extent possible, private foundations—whether they focus on education, public health, economic development, or diversity, equity, and inclusion—should take a step back, assess their priorities, and ask if there is room for rural investment within their portfolios.

Can we—as a sector—accept that we are underinvesting in areas that greatly need our attention and support?

Wynn Rosser, PhD, is president & CEO of the T.L.L. Temple Foundation. Wynn is committed to collective impact and to improving education outcomes – especially for low income and rural students as well as to a regional approach to grantmaking and philanthropic leadership.