Influencing mindsets and mental models requires identifying what current mental models need to be shifted, targeting priority stakeholders for change, and designing strategies that involve target groups. The most effective practitioners, before seeking to influence the thinking of others, first examine their own beliefs and attitudes and their role in shaping the system.

We recently had the privilege to facilitate learning exchanges among systems change practitioners on exploring the ‘why,’ ‘when,’ and ‘how’ of shifting mindsets as part of systems change, in partnership with Porticus. In this blog, we share insights from these exchanges alongside FSG’s experience in systems change to go a little deeper on the ‘mental models’ element of ‘The Water of Systems Change’ framework, exploring strategies and best practices from experienced systems-change agents.

Shifting mental models is a prerequisite to achieve systems change

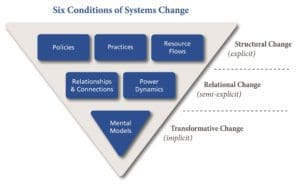

A system is a set of interconnected, interdependent, and interacting parts that form a complex, unified whole. Social Innovation Generation in Canada defines systems change as “Shifting the conditions that are holding the problem in place.” In our Water of Systems Change report, we lay out six conditions, from explicit funding flows to semi-implicit conditions—such as relationships—to implicit conditions, namely ‘mental models.’ So, what are mental models and why are they important to be aware of when striving for systems change?

As defined in the report, mental models are “deeply held beliefs and assumptions and taken-for-granted ways of operating that influence how we think, what we do, and how we talk.” They relate to stereotypes that ultimately dictate one’s thoughts and actions. Shifting mental models is a prerequisite to achieve systems change and relates to power dynamics and broader social norms. As noted, “Most systems theorists agree that mental models are foundational drivers of activity in any system…Unless funders and grantee partners can learn to work at this level, changes in the semi-explicit and explicit levels will, at best, be temporary or incomplete.”

Where to start?

Focusing on mental models can be particularly relevant if practitioners or community members observe that progress is stalled by counter-productive assumptions held by key actors needed for change to be achieved.

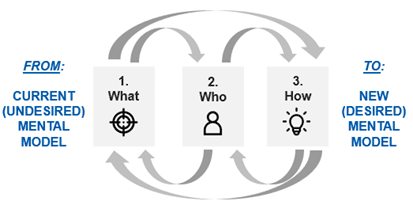

For practitioners, it can be helpful to consider approaching shifting mental models ‘from’ the perceived current state ‘to’ a desired future state. One way is to consider the following three elements when shifting mental models:

- What: Start by generating hypotheses on both (a) the current mental model(s) that are holding back progress, and (b) the desired mental models, perceptions, and beliefs that would unlock change, surfacing why this new situation would create progress or at least stop preventing it. This should be done involving a broad and diverse group in order to encompass and take into account different perspectives.

- Who: Identify which stakeholders hold that mental model and are the main target for change.

- How: Design strategies to influence mental models, beliefs, and behavior among these target stakeholders.

Developing strategies for shifting mindsets and mental models is an incremental and iterative process (See Figure 1). The process includes identifying a problem and exploring and adapting potential solutions.

Multiple mental models often co-exist; stakeholders do not always have clear visibility (or the right assumptions) on which model is problematic and hinders progress and should therefore be targeted for change. Experimentation, learning, and adaptation are keys to factor in new information generated along the way, including to validate or amend hypotheses and re-consider priorities accordingly.

Figure 1. Shifting mental models is an iterative process

Five principles emerged from practitioners’ experience related to shifting mental models:

#1: Change agents, within the philanthropic sector and beyond, should start by exploring their implicit beliefs.

Everyone has different beliefs and levels of influence—as an individual, a family member, a community stakeholder, an organization staff, or as an actor of the philanthropic sector. Change agents, including foundation and nonprofit practitioners and executives, community members and leaders, and activists, can start by exploring their own mental models, alongside that of their organization, and question what implicit beliefs and biases influence thoughts and actions. This requires reflecting on what can be done to inform, challenge, and adapt personal mental models. Change agents can seek to identify different viewpoints and explore various data sources, be open to discovering that their assumptions are not correct and flip their thinking to allow other things to be in the center verses the periphery.

- For instance, in the energy sector, actors make assumptions on why solutions often fail, influenced by their own mental models—regularly leading to misconceptions. SELCO Foundation has often witnessed the common (inaccurate) perception that target groups or consumers are “too poor” for the available solutions, which is not true. In reality, the solutions that investors are supporting are sub-optimal and over a period of time do not meet the expectations of target consumers, who choose not to further invest in them or recommend them to others. Without this understanding, investors will continue to support sub-optimal solutions which fail to gain traction.

#2: “Target groups” are co-creators, innovators, and potential investors in the solutions.

Partnering with “target groups” intended to ultimately benefit (for instance, people with lived experience of the topic, those at risk, or a target consumers or “end-users” for a new “affordable” climate resilient technology) can more effectively help to identify the mental model(s) that needs to be influenced to unlock progress and to determine the new, desired mental model(s). Defining the problem statement together, harnessing target groups’ deep understanding of the root causes alongside co-creating solutions, both drives towards a more effective solution while also shifting practitioner and target group mental models. These solutions must be adapted to specific context to ultimately sustainable and—if appropriate—scalable.

- In the energy sector, solutions often fail because they are inadequate, not adapted to the potential users and their context. While these solutions are designed, the focus is more on decreasing costs and maximizing scale (which are impact metrics for CSOs, philanthropies, and investors) rather than understanding and addressing the needs and aspirations of end users. Challenging widespread mental models is core to the SELCO Foundation approach. To develop adequate solutions, they partner with end users in defining the problem statement and then validating the features of the solutions developed. In SELCO Foundation’s experience, the problem statements co-developed with end users in this manner lead to a better understanding of aspirations, as well as the understanding on feasibility and viability of solutions as prioritized by the end users. This approach also comes from shifting another deep-rooted mental model, that end users know their problem statements, and also know the pathway they need to take to develop a solution. The gap in achieving that is the right resources, capacity, and technical knowledge.

#3: Stakeholders holding power should be the first target for change.

Decision makers and other stakeholders in a position of power should be priority target for change. Practitioners can explore and leverage different parameters to drive change amongst them, including to ensure target stakeholders feel responsible and accountable for change, and act upon these responsibilities. Strategies can include aiming to understand what influences powerful stakeholders’ thoughts and behaviors, reflecting on the extent to which current programs intentionally seek to influence this set of stakeholders, and adapting or designing strategies that leverage the unique organizational assets and capabilities of the intervening practitioner. Adapting messages, narratives, and overall storytelling for the target stakeholders will be an important dimension of all strategies.

- Take Dream a Dream. Their goal is to shift mindsets in the education sector in India to consider education as a stepping stone towards thriving and offering opportunities to build soft and life skills. Dream a Dream works with different stakeholders at various levels, including children themselves, but also governmental educational agency actors, to continuously nudge and shift narratives and perceptions through showcasing their in-school and out-of-school solutions.

#4: Mindset shifts can be achieved through strategies targeting different levels for change

Practitioners should consider different levels at which to develop their strategies for shifting mental models. One strategy is to directly engage and work at the level of the individual. Directly engaging individuals who are targets for change, such as parents or partners for instance, is one approach to shifting perspectives. In tandem, to achieve sustained shifts in perspectives, it is also important to also target shifts at the level of community or institution. Strategies that focus on shifting mindsets within communities and institutions (these may be physical or virtual) serve to be mutually reinforcing of targeted individual behavior change, shifting collective mindsets and perspectives, ideally serving as a precursor to influencing formal and informal policies and practices to be more conducive to the desired change. A final strategy is to strive for shifts at the level of the population (e.g., national change). Striving to shift mental models and mindsets at a population-level, such as through national campaigns and advocacy, can also serve as a powerful strategy, such as is seen in nationwide public health campaigns. Such population-wide narrative shifting campaigns can be leveraged alongside more localized and targets strategies with sub-groups of the population during the right ‘windows’ of opportunity in public sentiment. (For more on narrative shifts, see also “Shifting Mental Models to Advance Systems Change,” a Collective Impact Forum, FSG, and New Profit webinar).

- The H3 (Heads, Hands, and Hearts) Program, led by Porticus and Diktya Foundation, aims to act against violence against children including through prevention. Strategies focus on shifting mental models at multiple levels. At the individual level, the team focus on raising awareness and understanding that abuse against children exists and that there are different ways to protect children. At the level of community or institution, strategies focus on recognizing that abuse against children can happen within any organization and securing an explicit commitment for such abuse to be unacceptable. At the population level, the Foundation advocates to influence wider cultural shifts, including challenging the normalization of violence against children in society, to drive shifts in policy and practice.

#5: Influencing mental models is most effective when creating proximity between stakeholders, particularly those holding different perspectives and world views.

Influencing mental models requires time and space. This is crucial not only to allow for individual reflection but also for target stakeholders to experiment and/or see change. Experience is a powerful way to shift mindsets; practitioners should create space for stakeholders to connect, build relationships, and collectively explore and question mental models. Moreover, creating opportunities for different stakeholder groups to interact, including through unofficial exchanges, can be very effective. Working with champions and early adopters (including building capacity and creating platforms to engage with those in decision-making positions and positions of power) as well as with people with lived experience are also helpful to drive change—including for target audiences to ‘see’ change.

- Take Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE), for instance. Working at a global and interagency level, the INEE aims to create opportunities for actors in the field of education in emergencies to come together with their motivation, ideas, and priorities around a common cause—and take some time to have important conversations and reflect together.

Shifting mental models is an art, not a science. Therefore, there is an indefinite number of possible strategies to approach this complex challenge. We hope that the principles laid out in this article can trigger practitioners’ reflections and serve as a starting point as they further think about how to tackle mindset shifts and make mental model change happen.

We encourage funders to reflect on the fact that project-based approaches and grant processes do not always offer enough flexibility to focus on and monitor mental model shifts. Example challenges include the widespread habit to offer short-term (six month or one year) grants verses multi-year grants; funders’ requirements to show impact quickly verses the time truly needed to achieve meaningful change; and the limited ability to change the focus of a project or strategy as new insights and lessons emerge.

We encourage practitioners to explore, experiment, and reflect—including with peers—to find their own way to envision shifting mental models. Influencing minds is an incremental and iterative process, and strategies should evolve constantly based on learning and reflections on what is working and not working, and what could or should be done differently.

Thank you to Porticus partners that shared their experiences as part of this learning exchange:

- SELCO Foundation, which seeks to inspire and implement socially, financially and environmentally inclusive solutions by improving access to sustainable energy.

- Dream a Dream, a nonprofit organization that empowers children from vulnerable backgrounds to overcome adversity and thrive in a fast-changing world. As a pioneer of life skills in India, they are working to transform the education experience for 260+ million school-going children.

- The Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE), an open, global network of members working together within a humanitarian and development framework to ensure that all individuals have the right to a quality, safe, relevant, and equitable education.

- The Harvard Ecological Approaches to Social-Emotional Learning (EASEL) Laboratory, that explores the effects of high-quality social-emotional interventions on the development and achievement of children, youth, teachers, parents, and communities.

- Diktya Foundation, which focuses on children’s rights and the child protection challenge.

Porticus is a philanthropic organization focused on creating a just and sustainable future where human dignity flourishes. Porticus’ work aims to strengthen the resilience of communities so that all people have ownership over their future. To bring about system-level change, the foundation develops collaborative programs with partners, guided by participation, flexibility, and continuous learning.