Funders at the forefront of advancing systems change are shifting from being at the center of social change efforts to being a facilitator, connector, and learner in a larger ecosystem of actors who are working to create lasting, systems-level change. This trend has been underway for some time, but we are encouraged to see increased momentum in recent years inspired by the work of the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project and others. Many funders have embraced trust-based practices as a way to reshape power dynamics in the traditional funder-grantee relationship, while others are extending these principles to funders’ relationships with the systems they seek to transform. This is more than a shift in power between funders and grantees, but a strategic redistribution and application of power, including the power of others, across an ecosystem to create change.

By applying the principles of trust-based philanthropy to navigate relationships across a wider ecosystem of stakeholders, funders can redefine their role in advancing systems change. Instead of seeing themselves as the central focus, funders become one component of a larger ecosystem. This ecosystem approach fundamentally changes the work of funders, and influences how they conduct strategy development, implementation, and learning and evaluation alongside grantees and partners.

Developing strategy

One of the most basic misperceptions (and sources of critique) around trust-based philanthropy (TBP) is that it dismisses the importance and value of strategy. There has been much written recently about the fallacy of this perceived contradiction, emphasizing that TBP is strategic. We wholeheartedly agree.

One of the most basic misperceptions (and sources of critique) around trust-based philanthropy (TBP) is that it dismisses the importance and value of strategy. There has been much written recently about the fallacy of this perceived contradiction, emphasizing that TBP is strategic. We wholeheartedly agree.

Strategy involves answering fundamental questions about which issues a nonprofit or foundation aims to address, why these issues are chosen, how the organization is approaching creating change in those areas, and the expected impact of these efforts. These fundamentals are essential to providing direction to an organization’s work and are essential for enabling trust and collaboration between organizations because they allow for effective communication and mutual understanding of each other’s work.

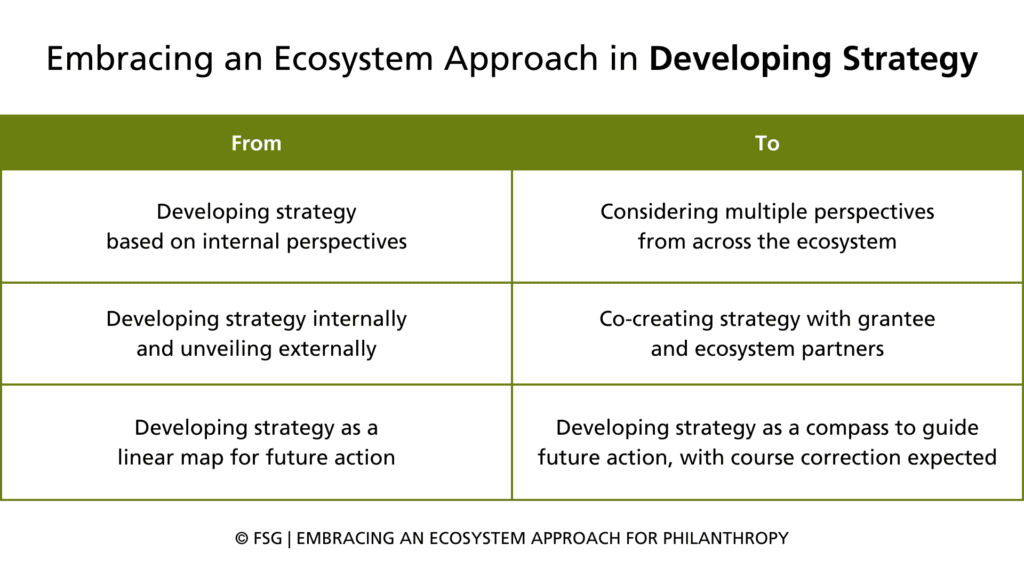

The challenge is that funders and nonprofits are working in complex and rapidly changing environments where no single organization or individual has access to all information and does not have control over all the actors in an ecosystem. As a result, it is often impossible to develop a strategy that will provide step-by-step instructions to a desired outcome, and so solutions must be adaptive. Strategy in complex systems must serve as a compass instead of a map, laying out a clear direction and focus for the work and then enabling learning and course correction along the way. Traditional strategy tools like theories of change can be helpful for getting internal and external alignment on how funders and their partners anticipate change could happen, but they must be treated seriously as the theories that they are and regularly re-examined and adjusted based on new information and shifts in the field.

For funders focused on systems change, applying trust-based principles to the strategy setting process is imperative for navigating the complexity inherent in systems. When developing a clear focus to guide their work, it is critical for funders to consider multiple perspectives, particularly from those who are closest to the problem (e.g., grantees, community members). Natrona Collective Health Trust, the largest health conversion foundation in Wyoming, set out to build a new philanthropic institution centered on the belief that the community owns and informs their work. In addition to engaging community members and leaders during the strategic planning process, they continue to find new ways to ensure that community voices are represented in the foundation’s daily operations. They have created a program advisory committee composed of paid community members and have engaged youth in participatory grantmaking.

Beyond the insights that can come from incorporating multiple perspectives in strategy development, the relationships formed through a collaborative or participatory strategy setting process are equally significant. Recently, the Texoma Health Foundation, a regional conversion foundation serving 4 counties across north Texas and southern Oklahoma conducted a strategy development process that incorporated community sessions in each of the counties it serves. In addition to providing input to the strategy, these sessions expanded and deepened the Foundation’s relationships across the community and introduced the Foundation to new networks that will be close partners in implementing the strategy.

Implementing strategy

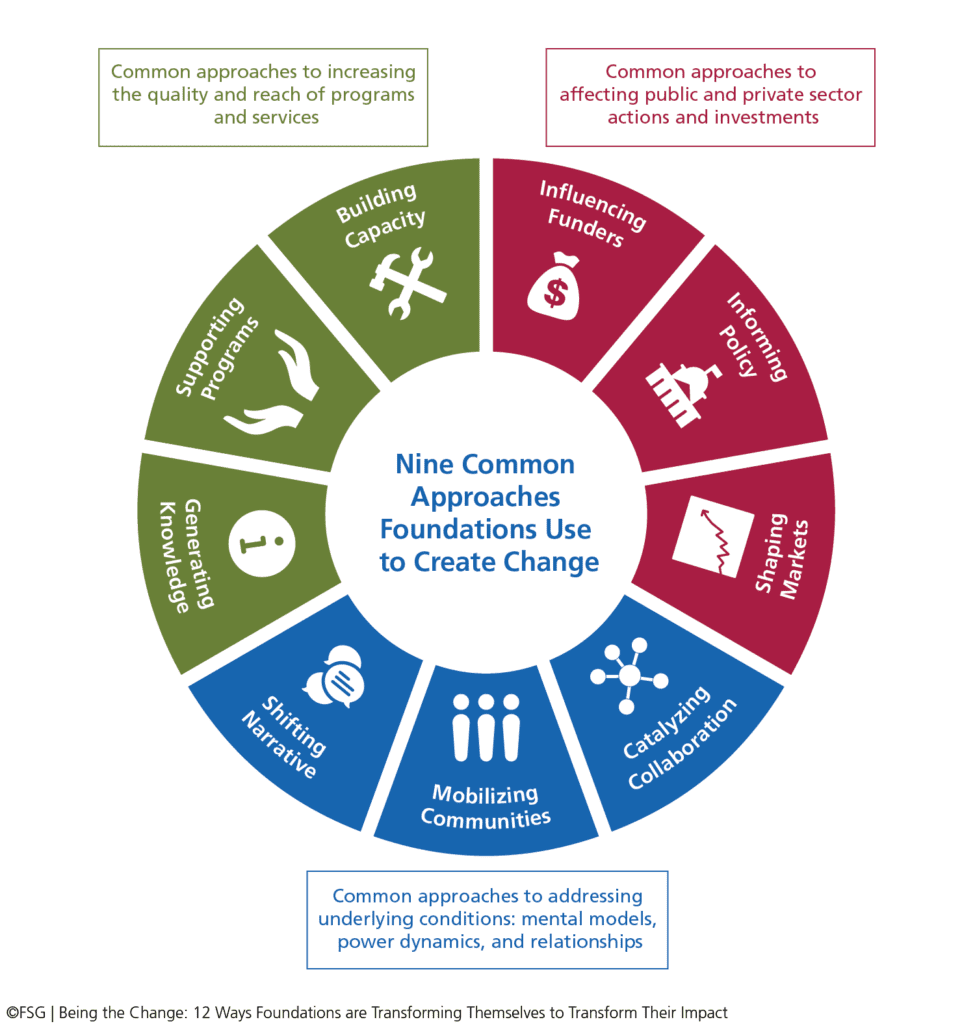

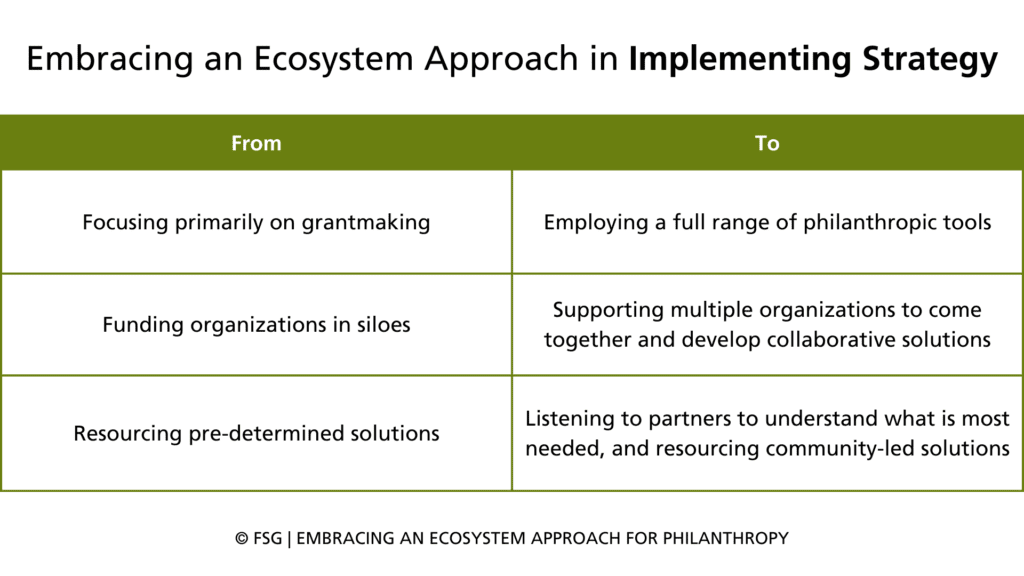

Once funders are clear about the focus of their work (the “what”), it is important to be clear how they will work to create change and what types of systems change they hope to influence. Informed by their grantees and the ecosystem of partners, funders can use a range of approaches, as referenced in the diagram below, from increasing the quality and reach of programs and services, to affecting public and private sector actions and investments, to addressing underlying conditions such as mental models, power dynamics, and relationships. For many foundations, it is helpful to build an intentional portfolio of approaches that reinforce one another, and which intentionally cede, share, and wield the power of the foundation in support of community priorities.

Once funders are clear about the focus of their work (the “what”), it is important to be clear how they will work to create change and what types of systems change they hope to influence. Informed by their grantees and the ecosystem of partners, funders can use a range of approaches, as referenced in the diagram below, from increasing the quality and reach of programs and services, to affecting public and private sector actions and investments, to addressing underlying conditions such as mental models, power dynamics, and relationships. For many foundations, it is helpful to build an intentional portfolio of approaches that reinforce one another, and which intentionally cede, share, and wield the power of the foundation in support of community priorities.

The role of the funder in strategy implementation is not to be prescriptive about specific solutions, but rather to be a partner and a deep listener with grantees and community partners on what is most needed and when. Systems change funders understand that those closest to the problem have the deepest knowledge of solutions, and frequently focus on building community power, ensuring that civic infrastructure includes marginalized voices, and funding community-driven solutions.

Funders can be helpful connectors and bring together different actors who hold different parts of the solution, and to provide resources quickly where they are most needed. We see this frequently play out in collective impact initiatives. For example, in 2018 Houston Endowment invested in bringing together organizations from across Houston who had a stake in increasing equitable civic engagement in the city, including issue and community focused advocates as well as organizations focused on civic engagement broadly to establish a shared vision and strategy for strengthening civic engagement in the city. The resulting initiative, Houston in Action, has emerged as an adaptive and resilient network of grassroots leaders, community-based organizations, academics, and foundation partners that has coordinated systemic responses to emergent civic challenges and opportunities, including electoral participation and democracy, the census, and coordinating policy advocacy. Houston Endowment played an important role in creating the space for leaders across the community to build relationships and trust among one another, and then in resourcing the priorities identified by the group and its ongoing operations.

Another example is the Danville Regional Foundation, which serves the Dan River region of Virginia and North Carolina. After having seen success in a Health Collaborative it had supported, the Foundation has aimed itself toward the goal of not having any grants come before the board that haven’t already been vetted by the community. To accomplish this, the Foundation invested in the formation of community councils, first by working with residents to define neighborhood boundaries as they were seen by the community, and then by identifying assets and community leaders in each neighborhood. Once the councils were established the Foundation gave them grant-making authority, guided by a belief that the communities wouldn’t be able to build leadership skills without the ability to lead. Additionally, the Foundation is supporting the formation of another regional Education Collaborative. Notably, the Foundation stays involved in decision making and contributes its own expertise and perspective to the collaboratives and councils but won’t fund anything that doesn’t have substantial buy in from the community.

Foundations can also work to shift power and systems by investing in the financial wellbeing and priorities of community residents themselves. For example, the Greater Washington Community Foundation is collaborating with workers, local government, and other partners to advance the guaranteed income movement, a proven strategy for promoting economic mobility of communities. The Foundation has now supported four pilots across the region, advancing the movement’s long-term vision of philanthropic dollars serving as the R&D and power-building muscle to influence and enact policy. Alternatively, The California Endowment’s Building Healthy Communities initiative was a more than 10 year statewide investment in building organizing power in specific communities experiencing deep health inequities to advance local and state policy change guided by the priorities of disinvested communities. The long-term arc of the initiative provided space for TCE to receive and respond to push back from grantees about its initially prescriptive approach. Through a more flexible and community-driven approach, the initiative has contributed to more than 1,200 policy changes across the state.

Learning and Evaluation

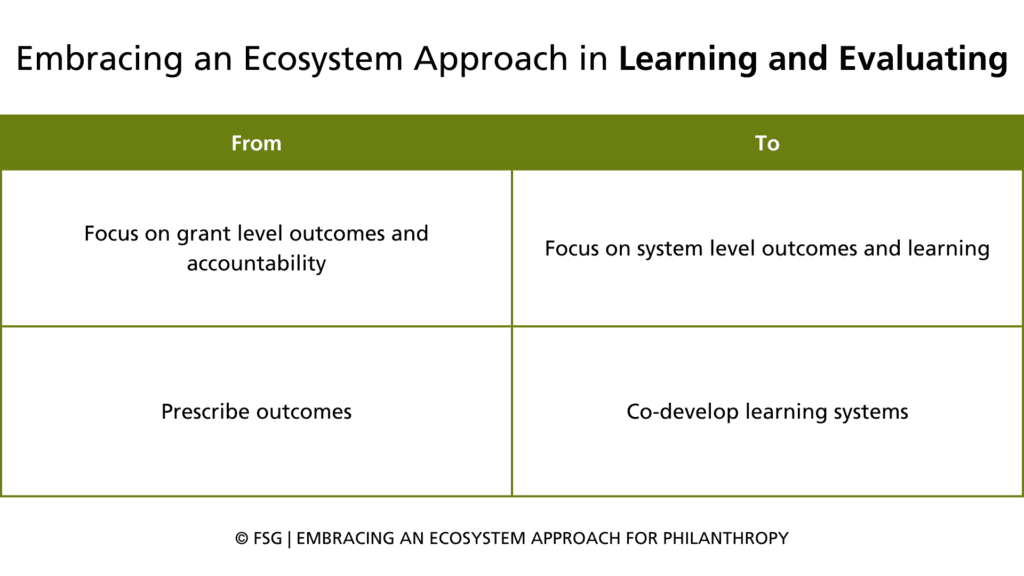

As William Bell, President and CEO of Casey Family Programs so clearly put it, “Systems level outcomes don’t happen on a grant level timeline.” For funders who take a systems-level approach and practice trust-based philanthropy, learning and evaluation can be one of the most challenging areas to navigate. Rather than focusing on holding grantees accountable or measuring their impact, these funders are using learning and evaluation to understand their effectiveness as a funder and to shape and continually adapt their strategy. Brenda Solorzano, outgoing CEO of Headwaters Foundation, articulates this approach clearly in her recent blog, and explains, “we did this by building a culture of trust and learning versus a culture based on accountability and impact alone. This required shifting paradigms of why we were evaluating, who the main audience for the learning was, who defines success and who bears the responsibility for collecting and analyzing data.”

As William Bell, President and CEO of Casey Family Programs so clearly put it, “Systems level outcomes don’t happen on a grant level timeline.” For funders who take a systems-level approach and practice trust-based philanthropy, learning and evaluation can be one of the most challenging areas to navigate. Rather than focusing on holding grantees accountable or measuring their impact, these funders are using learning and evaluation to understand their effectiveness as a funder and to shape and continually adapt their strategy. Brenda Solorzano, outgoing CEO of Headwaters Foundation, articulates this approach clearly in her recent blog, and explains, “we did this by building a culture of trust and learning versus a culture based on accountability and impact alone. This required shifting paradigms of why we were evaluating, who the main audience for the learning was, who defines success and who bears the responsibility for collecting and analyzing data.”

In re-orienting their approach to learning and evaluation from a grant-focused lens to a system-focused lens, funders can enable continuous learning not just for the foundation but for all of the other partners working on an issue. The Katz Amsterdam Foundation, which takes a systems-level approach to improving behavioral health in mountain communities, convened representatives across seven mountain communities to co-develop a shared measurement system for mental health and community well-being. In response to communities’ needs for more detailed and reliable data on mental health, the foundation has supported communities to identify shared measures, field annual surveys to collect data, maintain a public data dashboard that can be accessed in English and Spanish, and host annual convenings for communities to learn from one another.

Funders focused on equitable systems change can also benefit from the work of the Equitable Evaluation Initiative, which offers a valuable set of principles, orthodoxies, mindsets, tensions, and sticking points for funders to apply to their work. Equitable learning and evaluation also require a deep examination of funders’ own policies, practices, and cultures to ensure that they are not inadvertently creating harm, and to ensure mutual accountability with their partners.

At FSG, we continue to learn with our clients and the broader field about how funders can shift strategy development, implementation, and learning in the service of achieving lasting, equitable systems change. When we were founded over twenty years ago, our initial approach was rooted in traditional management strategy consulting approaches, and we have evolved our work significantly over the past two decades to center equity and to enable systems-level change. We continue to learn as the field of philanthropy continues to shift and evolve. We are encouraged to see a broad range of funders across size, geography, and foundation type embracing trust-based practices and new approaches to systems change. We are excited by how philanthropy is embodying a powerful shift from being the center of social change efforts—going from dictating top-down strategy, rigidly implementing that strategy, and evaluating at the grant-level with a focus on accountability rather than learning—to working in close partnership with the broader ecosystem of stakeholders necessary to sustain lasting change.