How can multinational corporate foundations develop an equity-centered, philanthropic strategy that is grounded in local context and communities while still being connected to a global theory of change?

Over the years, FSG has worked with many corporate foundations connected to multinational companies, including SAP, Mars, and Ares Management Corporation (Ares), to help develop and articulate their global philanthropic strategies. Building a global strategy is a crucial component of ensuring that the foundation’s activities are aligned with core business goals and relevant to employees around the world. However, the next step for foundations is to then develop localized strategies—whether they be city, country, or regional—that are based on the global philanthropic strategy while still being grounded in local context and informed by each of the distinct communities where the company is pursuing social impact.

Through these engagements, we have identified three lessons for global corporations and foundations to consider when building local (e.g. city, country, or regional) strategies for social impact:

- Utilize systems thinking to define your approach: Use systems thinking to map existing assets and opportunities across your company to define your unique capabilities and align on a shared vision for impact.

- Be responsive to communities by contextualizing existing barriers and opportunities: Conduct asset-based and equity-centered landscape analysis to understand both challenges and opportunities within your target issue area and geography and develop community-led and locally appropriate responses.

- Embed equity in action: Use targeted universalism as a framework to address the root causes of the barriers faced by the populations you serve and devise strategic approaches that are responsive to those specific communities.

Utilize systems thinking to define your approach

Use systems thinking to map existing assets and opportunities across your company to define your unique capabilities and align on a shared vision for impact.

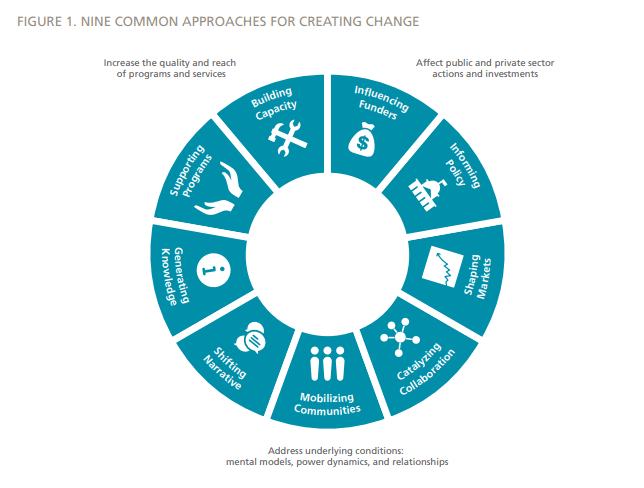

Nine common approaches to driving systems change, from FSG’s Being the Change report.

FSG often uses the Nine Approaches to Driving Systems Change (see page 11 of our Being the Change report) to ensure that our clients are leveraging systems thinking in their approach to social impact. We begin this process by mapping the approaches already being used within the organization and then identify which approaches are best suited for the client’s intended impact.

To leverage a systems change approach, a company should seek to understand which approaches they are already using, as well as which approaches are being used by other arms of the company or peers. Comparing this to the approaches needed to drive its desired impact; foundations can better understand how to refine their grantmaking approach to target the systems keeping inequitable conditions in place. Ensuring that a new philanthropic strategy is both locally rooted and globally connected is no easy feat, and this approach allows organizations to understand how the corporate foundation’s activities might intersect with other activities across the business.

Corporate foundations embarking on similar journeys should begin their process by similarly mapping the strengths, resources, and partnerships that exist across the corporation to foster alignment on the company’s intended impact. By doing this, the foundation can act as a manifestation of the company’s broader social impact vision and be a central point from which to leverage the assets of the company as a whole. This allows the company’s philanthropic vehicle to scale its impact beyond what would be possible using just its own resources as well as to have a clear global story of impact, aligned storytelling, and opportunities for learning across contexts.

Be responsive to communities by contextualizing existing barriers and opportunities

Conduct asset-based and equity-centered landscape analysis to understand both challenges and opportunities within your target issue area and geography and develop community-led and locally appropriate responses.

Corporate foundations should aspire to understand the unique assets, resources, cultural nuances, and expertise already existing in the regions and communities they seek to serve. Asset based framing, a concept coined by Trabian Shorters, is an important approach to landscape research that enables us to define populations not just by barriers they face but also by the potential, wisdom, resources, and existing cultural assets in those communities. Leveraging and amplifying communities’ unique assets can also help foundations avoid the trap of attempting to design a “solution” without the requisite historical and community context needed to effectively problem-solve.

Foundations should look for ways to add to or deepen the work of leaders with deep roots in their community and strong understandings of the unique conditions at play. Foundations can conduct rigorous research utilizing literature and existing data, ethnography, books, videos, documentaries, and more to deepen their understanding of populations in non-extractive ways that are not only quantitative, but also nuanced and comprehensive. Corporate foundations should also seek to determine the best approach to bring community voices and perspectives to their initial analysis and understanding of needs. This might include interviews or focus groups with community members, including local leaders, grassroots organizations, and practitioners, to understand the strengths and needs of individual communities. To help ensure this process is done equitably, foundations should compensate these community representatives for their time and for the critical insight that they are contributing to the strategy development process.

Foundations can also explore power-building solutions that deepen localized leadership through participatory grantmaking, leadership programs in targeted communities, or training that enhances the capacity of local offices or teams to conduct regional grantmaking. For example, FSG recently worked with Ares to develop regional grantmaking strategies for its corporate foundation alongside regional employee-led committees. This collaboration helped build on the firm’s culture of empowering employees to help drive positive change through community engagement and leadership. Michelle Armstrong, head of philanthropy and executive director of the Ares Charitable Foundation said, “FSG’s research and support for our regional employee-led grantmaking committees helped our team members understand how they can drive impact in alignment with our global funding priorities while also being responsive to causes and conditions in their local communities. It’s a delicate balance to wed organizational goals with multiple perspectives, but collaboration is true to how we operate as a firm, and it’s necessary to advance the Ares Charitable Foundation’s mission.”

Embed equity in action

Use targeted universalism as a framework to address the root causes of the barriers faced by the populations you serve.

Targeted universalism, a term coined by john a. powell of the UC Berkeley Othering & Belonging Institute, is an approach that involves setting universal goals that can be achieved by targeting the most disadvantaged people. For one recent client, applying targeted universalism meant focusing on the most historically marginalized populations in the U.S. We conducted research on existing discrepancies and used those discrepancies to identify structural conditions and barriers. This allowed us to understand the root causes of disparities and ensure that solutions were designed with these root causes in mind.

To utilize targeted universalism, foundations should seek to understand the barriers faced by the most marginalized of those they seek to serve. By addressing those barriers, foundations can help ensure that benefits and opportunities available for the broader population are accessible to those most marginalized. This concept is illustrated by the “Curb-Cut Effect,” originally described by PolicyLink Founder and former FSG Board Member Angela Glover Blackwell. Initially implemented to make sidewalks more accessible for people who use wheelchairs, curb-cuts are now a standard functional design element of sidewalks that many groups of people benefit from (parents with strollers, people with luggage, bicyclists, etc.). In this way, solutions to a barrier facing a marginalized group (in this example, people who use wheelchairs) benefit society as a whole.

As global corporate foundations become more sophisticated in their philanthropic approach, they can embed social impact across their philanthropic and business activities. By doing so, they can go beyond simply leveraging only foundation resources to harnessing the full breadth of resources available to them, including those of the parent company. At the same time, they must work actively to ensure that these strategies are rooted in local context and history in order to be effective in addressing root causes and disparities. While we have crafted individualized approaches for each of the clients we’ve worked with, we have found these three lessons helpful in considering how to build localized strategies for social impact that are also connected to a global whole.