In recent years, philanthropic funders have come to see the value in collaborating with one another to magnify their impact. Today we see all kinds of funders engaging with each other informally and learning from each other, and, increasingly, partnering in strategic funding together. In FSG’s experience working with funders, we have heard that committing to every collaboration opportunity can be overly time-consuming, especially for smaller funders with limited staff capacity. As invitations come across the desk, how can funders determine what collaboration opportunities will be most impactful?

Through our work facilitating and supporting funder collaboratives with strategic planning, we have observed that funders can take a strategic approach to right-sizing their collaboration by selecting what collaboration structures to engage in based on their organization’s strategic priorities and staff capacity.

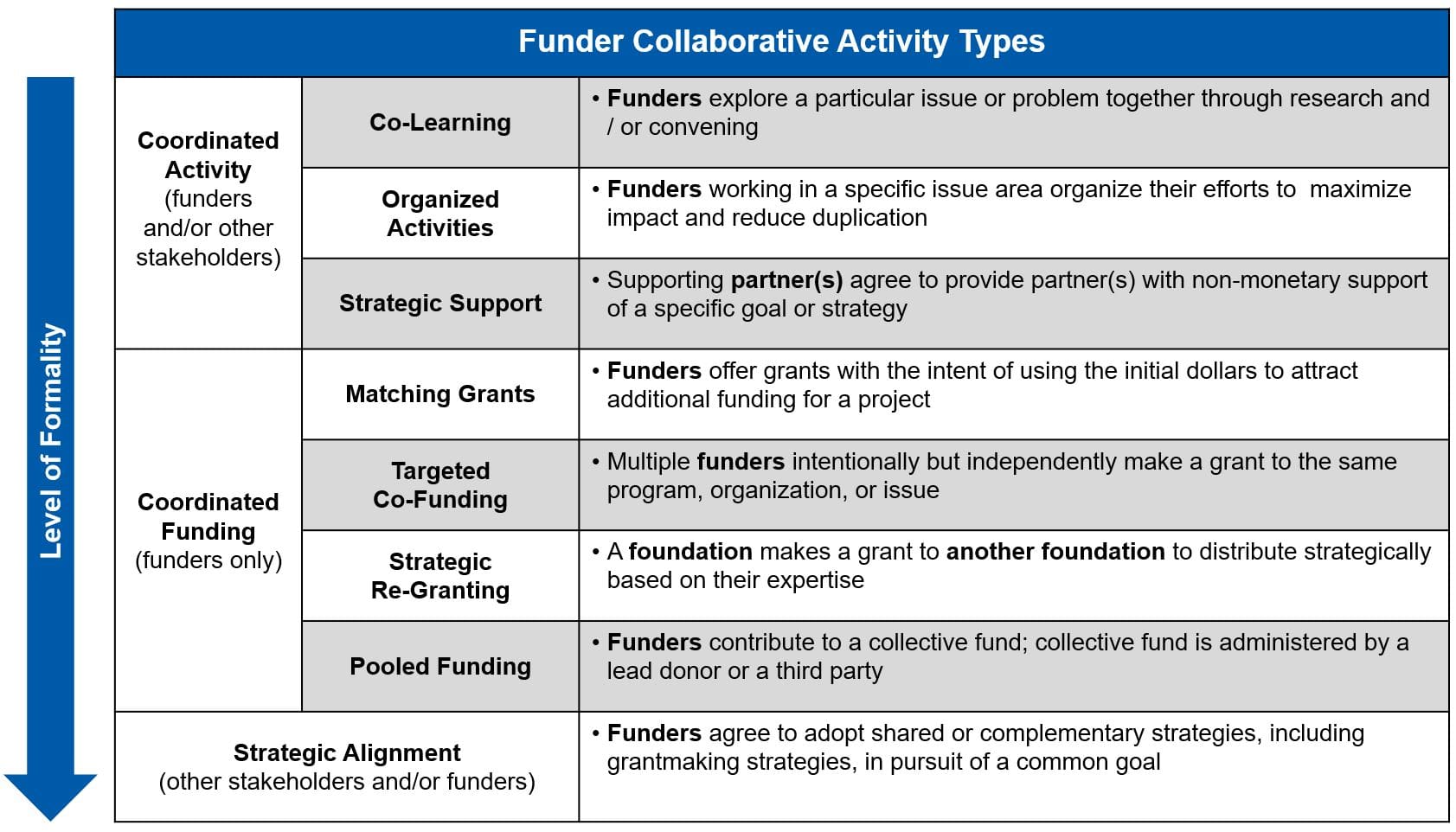

The first thing to keep in mind is that different collaboration approaches require varying levels of commitment and result in different benefits for participants. FSG has put together a categorization of funder collaborative activity types based on our own experience working with funders and an analysis of existing funder collaboratives in the U.S., across issue areas:

The above chart organizes activity types from informal to formal, with three main categories: coordinated activities, coordinated funding, and strategic alignment. Many informal spaces are centered around learning and allow for funders to exchange ideas or gain expertise through coordinated activities. On the other hand, more formal collaboration structures are required for coordinated funding, such as targeted co-funding, strategic re-granting, and pooled funding, or to develop strategic alignment.

Once funders better understand the collaboration opportunities in front of them, they can select collaboration commitments based on goals for their strategic priorities. As with any strategic decision, it is important to make decisions based on a clear purpose. Rather than signing up for every collaborative opportunity, funders should revisit their strategic plan to determine what collaboration approach is the best fit for them. For example, it would be very time-consuming and nearly impossible for most funders to engage in strategic alignment collaboration activities for every area of their strategy. At the same time, funders are missing out on valuable benefits if they only collaborate through co-learning or information exchange. For the most impactful approach, funders should engage in different types of collaboration based on goals for their strategic priorities.

If funders are exploring a new issue area or strategic pillar, it can be very valuable to engage in coordinated activities where they can learn from other funders in the space and other stakeholders, such as beneficiaries and community members. Still, funders should pause to determine what level of commitment is strategic. They may want to maintain connections to learning communities across their strategy but prioritize participation in areas where learning is most needed.

So, when should funders dive deep into activities like pooled funding and strategic alignment? More intensive collaboration can be especially impactful for strategies oriented toward longer-term systems change. With many funders orienting themselves towards these ingrained problems, more formalized collaboration provides an opportunity to pool together resources to address complex and deep-rooted issues that they can only make a dent in when working alone. Pooled funds, which are administered by a lead donor or third party can allow funders to tap into expertise or ways of working they don’t have in-house. Some pooled funds, for example, have closer ties to beneficiaries, local community organizations, or community organizers. To determine what collaboration activities to engage in, funders should go back to their strategy and goals. Where in their strategic priorities are they focusing most on systems change, and where can banding together with other funders or experts move their goals forward?

In our work, we have seen how the time commitment required by funders for collaboration can vary across levels of formality. Some informal spaces can be more time-consuming than expected and require time at events or meetings and support for the backbone or planning of meetings. Some forms of coordinating funding such as matching grants can be less time-consuming, as they mostly require internal alignment.

When considering collaboration opportunities, funders must prioritize staff capacity to get the most value out of collaborative commitments. Collaboratives are not successful when members do not have the capacity to engage in necessary activities, meetings, or decision-making, and funders do not get value out of the experience if they can’t participate in key activities. When setting up a collaborative group, leaders or members should be clear about the expected time and resource commitment, and they should consider setting up different levels of membership that would allow potential members with a smaller staff or less time capacity to participate. At the same time, funders considering joining a collaborative are responsible for ensuring they have the capacity to engage before getting on board. It can be tempting to sign up for every opportunity to ensure one stays in the loop, but doing so can cause more trouble than good, when staff find themselves overburdened, not meeting collaborative expectations, or attending very few sessions.

As with any strategy, a funders’ approach to collaboration should be subject to change. The organization’s strategic priorities may change, or staff capacity may change. Funders should be prepared to take an adaptable approach and be flexible about adjusting collaboration commitments. For example, if staff capacity is low, collaboration may not remain a priority. Or, if an issue area increases in its level of strategic importance to the organization, funders can consider investing in more formal collaboration approaches for that issue area.

This article was written by Camila Novo-Viano and developed through the contributions and input of: Kendra Berenson, Jeff Cohen, Tori Fukumitsu, Megan Linquiti, Ruchi Nadkarni, Njideka Ofoleta, and Robert Wilkes.