As a recently promoted vice president of sustainability at a global food company, a long-standing FSG client called me to discuss how to get her business to act on new and bold sustainability goals that range from climate action to healthier products. Her company is driven by a strong social purpose: a core value is that both the company and the stakeholders should profit from the company’s operations and investments. At the same time, the business is facing a particularly tough cycle and management is very focused on improving financials in the short-term.

I offered 2 recommendations to help reconcile these apparently contradictory demands on the business:

Help the business help itself

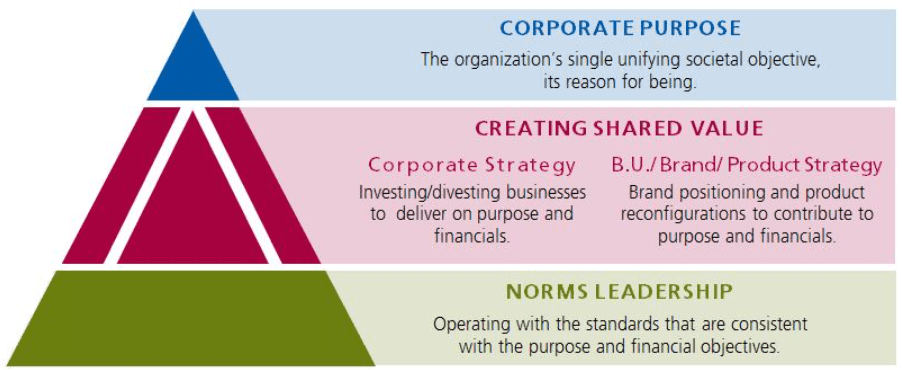

Sustainability and CSR leaders cannot carry the full burden of advancing sustainable policies and practices at their organization—they should serve as catalysts for company-wide action. Delivering on a social purpose and bold sustainability goals is everyone’s job. That means that all employees from entry-level to the C-suite need to understand how their decisions can—and must—help advance the company’s social agenda. Corporate decision-makers should consider how acquisitions or divestments help advance societal as well as financial objectives, while business unit management can think about how developing new products can achieve these results.

Guiding decision-making at all levels of the organizations is the job of sustainability leadership. My advice for the new vice president was to work with human resources leadership to capture, for each job family in the business, the types of decisions that would help the company meet its bold goals, and to illustrate them with stories that help all employees see how each narrative relates to their daily work. The sustainability team can help drive an internal education campaign using both virtual and live channels to influence practices throughout the company.

Guide decision-making to prioritize major corporate initiatives

At the same time, I advised the vice president that she should provide corporate leadership with a clear set of choices concerning existing and new sustainability initiatives, in a way that recognizes the tension between short-term financial targets and creating value for all stakeholders over the long-term.

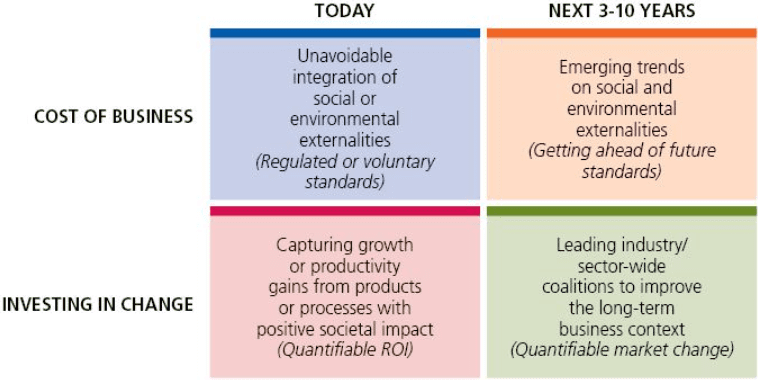

Concretely, this means adding a financial dimension to the bold sustainability goals and clearly differentiating between potential investments that relate to the cost of doing business and investing in business models and context that can grow the business as well as benefit society (image below).

The key message to senior colleagues is that many goals can be pursued not as the “societal cost of business,” but as “purpose-guided investments.”

On the cost side, not all initiatives are equal. Some company footprints (or externalities) are regulated or becoming de facto standards—like ensuring food quality standards or paying a waste or water tax. The cost of these externalities is already internalized or unavoidable. These should be considered separately from emerging and potential costs of doing business around, for example, issues such as obesity, deforestation, or workforce health, where pressure is mounting for companies to account for their contribution to these societal burdens. The issues that could cause the greatest future costs to the business are likely worthy of prioritization in terms of research and early mitigation, even in times of scarcity.

On the other hand, evidence across industries clearly suggests that many sustainability efforts are also profitable, such as product renovations for healthier consumption or gaining energy and climate-friendly efficiencies. Guided by purpose, these investments should be prioritized over other profitable investments that deliver no or less societal benefits.

The long-term and inherently riskier contextual investments—like building the political will to favor green technologies or investing in a health awareness campaign—need to be compared against the potential market upside for the company. If the intervention has a reasonable chance of changing market conditions at a scale that matters—most likely by mobilizing cross-sector co-investment— then again, such commitments should not be considered in the “societal cost of business” bucket.

Even in times of scarcity, the best companies remain committed to sustainability, investing smartly among a portfolio of options and empowering all employees to play a part.