Beyond Infrastructure: Why the WASH Sector Needs Local Private Providers to Reach the Underserved

Our experience shows that formal partnerships with local WASH providers can serve three to four times more people per…

At FSG, we believe in the power of place-based philanthropy to address systemic, historic inequities rooted in place. To advance systems change, many funders are recognizing the importance of going beyond traditional grantmaking to being facilitators, connectors, and learners in a larger ecosystem of actors necessary to sustain lasting change. At its heart, place-based philanthropy recognizes that funders are just one player in a larger ecosystem of stakeholders contributing to a place, and that cross-sectoral collaboration and community leadership are needed to advance long-term, sustainable change.

Since the earliest days of philanthropy, funders and donors have mobilized to support the regions that they live in. Place-based giving is not a new concept, but recently we have seen more funders reaffirm their commitment to places as units of change. As funders go deeper into their commitments to place, we wanted to share insights to support them in being more intentional and impactful in their place-based philanthropy. This piece is for the numerous private, community, health conversion, family, and corporate foundations already funding in place across the United States but who could deepen their impact through more community-driven and systems change approaches.

There is no singular definition of place-based philanthropy, but for this article we are referring to funders who invest in service of a defined location such as a neighborhood, city, state, or region. Geographic context is key to place-based philanthropy, requiring an examination of the unique histories that contribute to inequities in place. At its best, place-based philanthropy is characterized by a long-term presence and relationship with communities in a specific region and collaboration with other local partners across sectors.

While many funders don’t necessarily think of themselves as place-based funders, many are eager to see impact in a specific geographic region. Reasons for that commitment may vary—for example, community foundations and many family foundations are organized around defined geographic areas in response to a sense of affinity, gratitude, and duty to the local community. Healthcare conversion foundations are often legally bound to serve the service areas of their founding organization or healthcare system. Corporate funders might be eager to give back to their hometowns and communities where they have significant operations, and private national foundations may have historic commitments to specific regions or cities based on their founders, and other funders focus on place as an extension of a broader strategy.

When it comes to place-based efforts, we believe that philanthropy has the opportunity to lean into the full suite of roles that foundations can play to create impact. “Philanthropy is about so much more than grantmaking,” said Chris Carlson, Managing Director at FSG. “Foundations and their staff occupy such a unique space in their communities, bridging sectors and levels of power, giving them great potential and responsibility to catalyze progress in their community in how they use their investments, influence, insight, and relationships.”

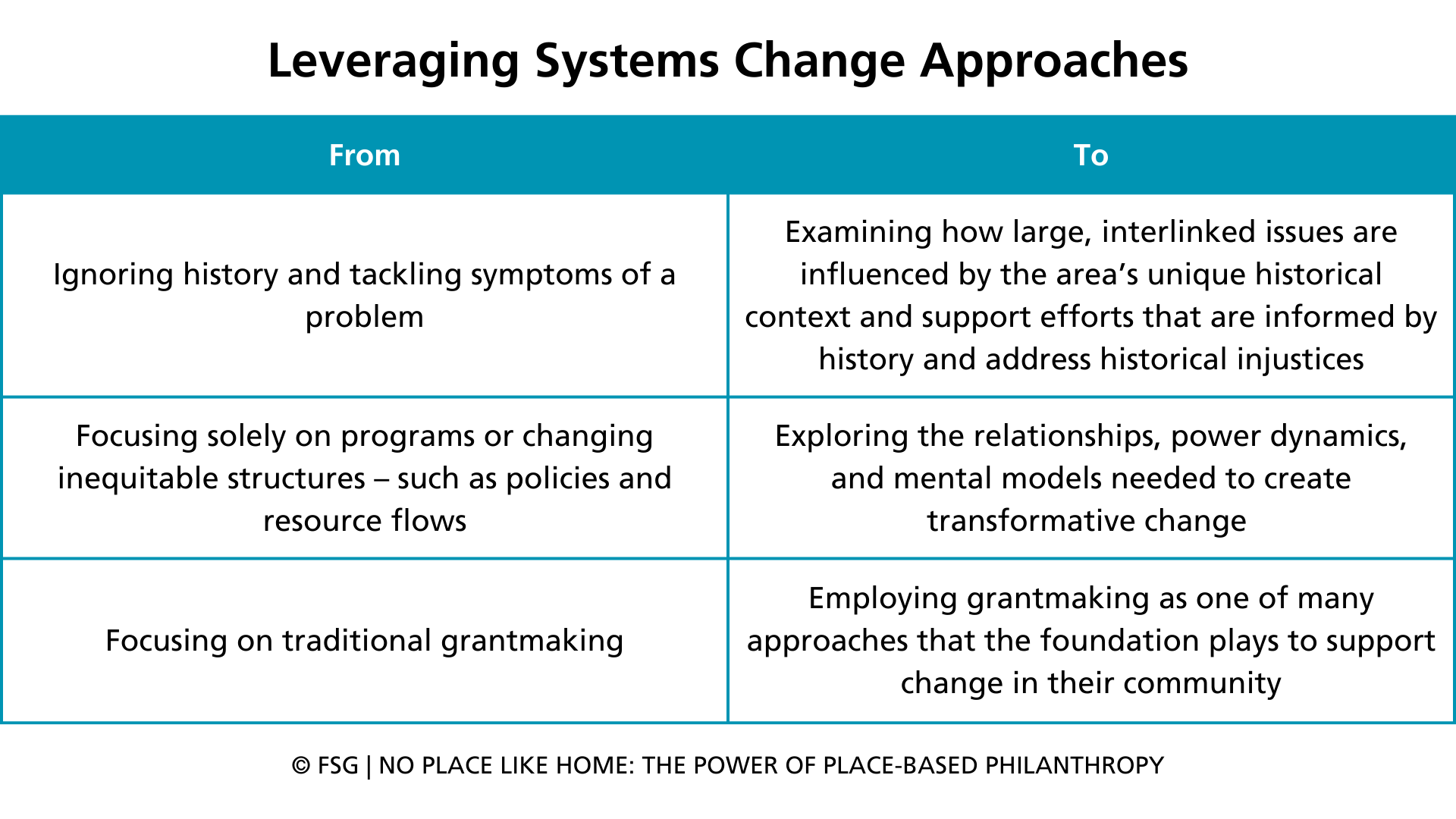

We believe that a focus on place is particularly conducive to employing systems change approaches. A place-based focus creates a useful geographic boundary on systems, allowing funders to examine how large, interlinked issues such as economic inequality, racism, and health inequities show up in their community and are influenced by the area’s unique historical context and ecosystem of actors.

We believe that a focus on place is particularly conducive to employing systems change approaches. A place-based focus creates a useful geographic boundary on systems, allowing funders to examine how large, interlinked issues such as economic inequality, racism, and health inequities show up in their community and are influenced by the area’s unique historical context and ecosystem of actors.

“History is a determining factor of today’s inequities. Even when leaders grow up in a place and feel they understand it – things aren’t always as they seem,” said Fay Hanleybrown, Managing Director and Head of FSG’s U.S. consulting practice. “Many of the place-based funders we’ve worked with are increasingly analyzing the systems that contribute to today’s inequities in a particular place.”

At FSG, we often use a systems change triangle to help analyze the conditions holding a problem in place. When it comes to changing systems, we often think about changing inequitable structures—such as policies, practices, or resource flows. However, focusing on place can help us to better focus on the relationships, power dynamics, and mental models needed to create transformative change. The elements of systems are often more tangible and navigable in a place-based context, where the actors are not abstract institutions but are often individual people, and the relationships are interpersonal.

For these reasons, many see cities as the most dynamic laboratories for innovation and policy, as places where meaningful progress is not only possible but probable. For example, organizations like Living Cities and the Bloomberg Cities Network invest in cities and city leaders by strengthening their leadership, innovation, data, and collaboration skills. Similarly, many groups are committed to supporting the innovation and vitality of often overlooked rural communities. For example, the NFG Integrated Rural Strategies Group is bringing funders together to address local needs and gaps in rural organizing infrastructure and develop shared agendas to support rural organizing and justice-advancing efforts, and the Rural Community Assistance Partnership is a national network of nonprofit and technical assistance partners working to improve the quality of life in rural America with a focus on the environment and economic and community development.

For place-based funders seeking to more intentionally pursue systems change in their communities, we have distilled some common patterns among those who are not yet engaging in systems change and offer initial suggestions for ways of working differently:

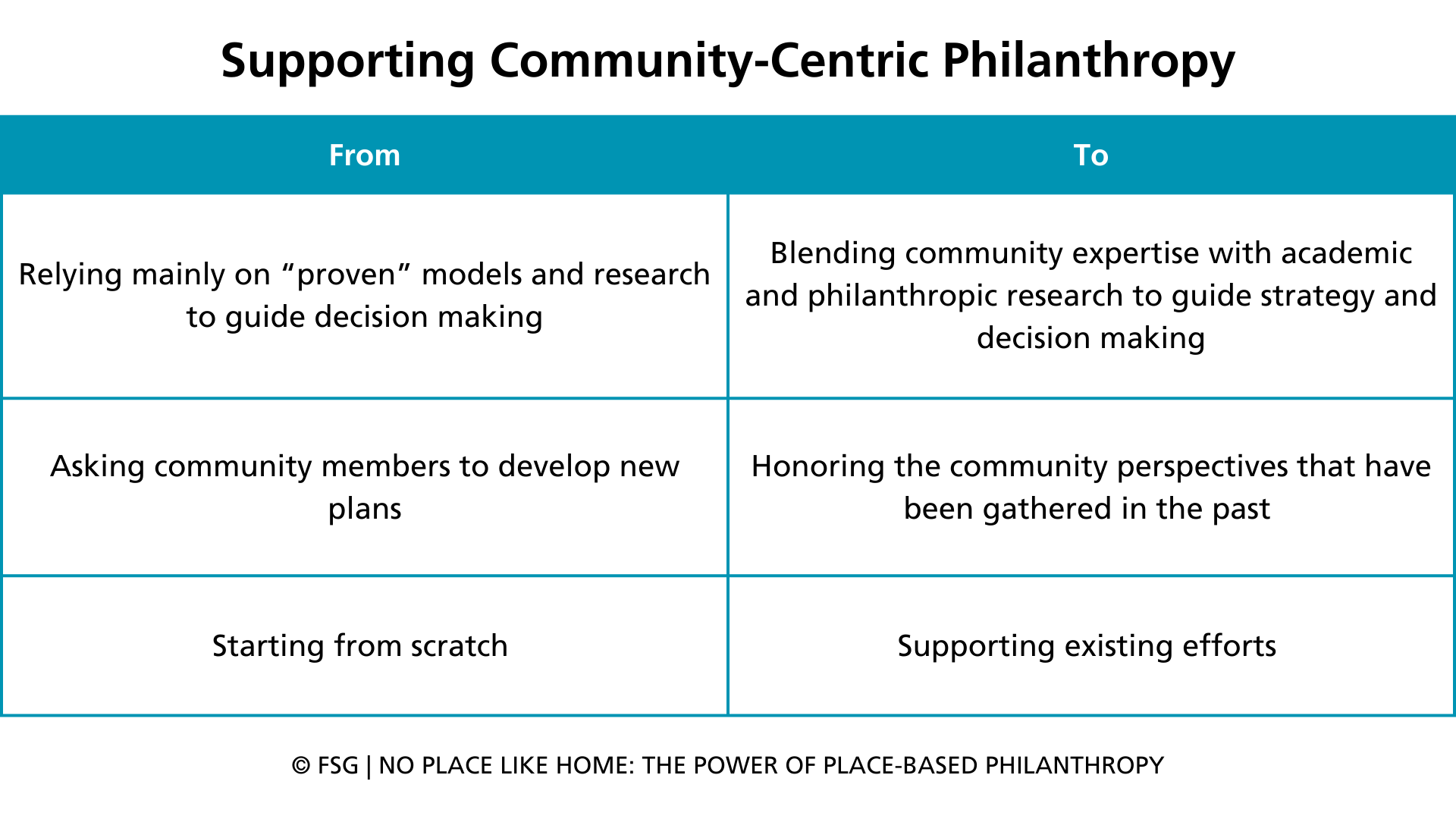

Place-based philanthropy is most effective when it recognizes and follows community wisdom and expertise. Often funders seek to solve problems or address issues by bringing solutions to the community based on models from other places or assumptions informed by academic research or reports from other philanthropists. While this kind of knowledge can be helpful, it is most powerful when combined with the leadership, expertise, and insights from those directly facing the issues funders seek to address.

Place-based philanthropy is most effective when it recognizes and follows community wisdom and expertise. Often funders seek to solve problems or address issues by bringing solutions to the community based on models from other places or assumptions informed by academic research or reports from other philanthropists. While this kind of knowledge can be helpful, it is most powerful when combined with the leadership, expertise, and insights from those directly facing the issues funders seek to address.

“Community wisdom is the heart of our most successful projects. The people experiencing challenges directly are the ones who best understand what is in the way and who must be at the center of any vision to create change,” said Miya Cain, Associate Director at FSG. “For example, when I worked on a youth mental well-being initiative, adults mostly wanted to focus on treatment and health care system related problems and solutions. However, after listening to youth, adults realized that young people are looking for support from their schools, community organizations, and caregivers at home. The initiative shifted to focus more on improving community conditions to foster youth well-being and ensure that youth continue to lead the development of solutions.”

Funders can work alongside community leaders and organizations by investing in existing projects and priorities and providing complementary capacity-building and operational support when appropriate. In some cases, it may be helpful to support new community-led research or planning processes to identify needs and opportunities for investment, but funders should recognize that many disinvested communities have been asked to do this work already, often multiple times, and often without follow through on resourcing from government or other funders. By leading with support for existing projects, organizations, and priorities, place-based philanthropy can be complementary to other practices such as trust-based philanthropy, participatory grantmaking, and asset-based community development that aim to address historic power imbalances in the funder-grantee relationship.

“There is a deep mistrust that exists between communities and institutions due to gaps of intentional place-based divestment,” said Waheera Mardah, Senior Consultant at FSG. “For place-based funders to be more intentional and impactful in their work, it is critical to listen to and be led by the community leaders who have existed and advanced change in spite of those challenges.”

Supporting existing priorities and leaders can help bridge mistrust and provide a foundation for long-term partnerships and relationship-building with communities. For place-based funders seeking to build or rebuild relationships with specific communities in their region, we recommend committing to a community-led approach. This may require adopting different ways of working, such as the following:

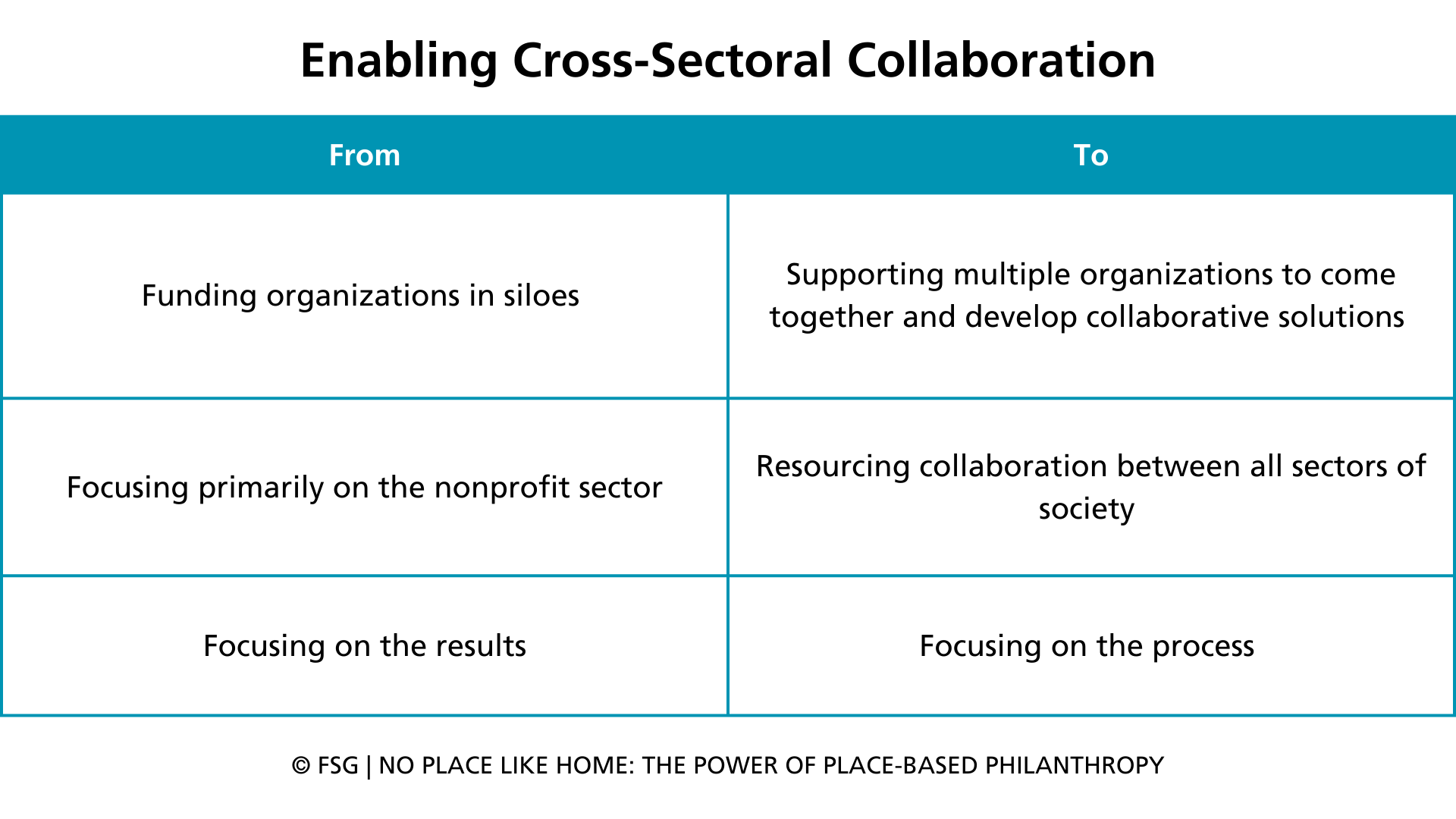

An important and often unique role for place-based funders is to bring together cross-sector leaders and community members that all care about that place. Few organizations have the resources, relationships, and interest to focus on sustaining collaboration. As we write in “Embracing an Ecosystem Approach for Philanthropy,” philanthropy is embodying a powerful shift from being at the center of social change efforts to working in partnership with the broader ecosystem of stakeholders necessary to sustain lasting change. Funders who embrace the power of cross-sectoral collaboration can play into their strengths as facilitators, connectors, and learners that enhance the efforts of other actors.

An important and often unique role for place-based funders is to bring together cross-sector leaders and community members that all care about that place. Few organizations have the resources, relationships, and interest to focus on sustaining collaboration. As we write in “Embracing an Ecosystem Approach for Philanthropy,” philanthropy is embodying a powerful shift from being at the center of social change efforts to working in partnership with the broader ecosystem of stakeholders necessary to sustain lasting change. Funders who embrace the power of cross-sectoral collaboration can play into their strengths as facilitators, connectors, and learners that enhance the efforts of other actors.

For example, the James S. McDonnell Foundation (JSMF) is investing in civic infrastructure and building the collaborative tables that their region needs after a recent strategic pivot to promote inclusive growth and shared prosperity in St Louis. As Dr. Jason Q. Purnell, President of JSMF noted at a recent plenary session at the 2024 Collective Impact Action Summit, “Collaboration has to be somebody’s job, and it has to be a well-resourced part of somebody’s job or else it doesn’t happen.”

Collective impact can be one approach to engaging partners across sectors in a structured way. Collective impact initiatives share a common agenda, shared measurement system, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and a backbone organization to organize collaboration. The Collective Impact Forum, an initiative of FSG and the Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions, provides resources, hosts learning events, and offers coaching to help advance place-based collaborative work.

In addition to the progress that cross-sector collaboratives can unlock in their chosen focus areas, community resilience is often built through the relationships and collaborative processes built through these partnerships. During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many collective impact initiatives pivoted to focus on sharing information and resources to meet community needs by leveraging long-established relationships and collaborative processes to enable a rapid response in an unprecedented time. For example, Milwaukee’s COVID-19 response showcased a remarkable mobilization of resources and organizations to address needs for shelter, food, testing, internet connection in a rapid amount of time. “What’s so essential about place-based philanthropy is that it builds the capacity for long-term, sustained community change,” said Jennifer Splansky Juster, Executive Director of the Collective Impact Forum. “Funders are supporting communities to organize when needed, regardless of the timing or challenge.”

“Focusing on place allows us to be more connected to communities and the lives of real people,” said John Harper, CEO of FSG. “Philanthropy has the opportunity to help build collaborative tables that bring together cross-sector leaders and help real people and communities to be better heard.” To embrace the power of cross-sectoral collaboration, funders must often embrace ways of working that are a departure from the status quo:

At FSG, we see place-based work as an essential systems change strategy. Having supported place-based efforts for over 20 years, we are excited to see funders of all kinds—including corporate, family, private, and community foundations working locally, regionally, and nationally— being more intentional and impactful in their place-based philanthropy. Funders are embracing the power of cross-sectoral collaboration and community leadership, going beyond traditional grantmaking to being facilitators, connectors, and learners in a larger ecosystem of actors contributing to a place.

Former Associate Director

Managing Director

Director of Programs & Partnerships

Managing Director

Managing Director

Executive Director

Chief Executive Officer

Former Associate Director

Associate Director

Our experience shows that formal partnerships with local WASH providers can serve three to four times more people per…

Evaluations, whether formative or summative, should be learning-oriented—helping funders and implementers adapt, avoid wasted effort, and strengthen real impac…

Funders working in the Global South can incorporate market-based solutions to widen the development resource pool and build pathways…

You will also receive email updates on new ideas and resources from FSG.

"*" indicates required fields

You will also receive email updates on new ideas and resources from FSG.

"*" indicates required fields

Get updates on new ideas and resources from FSG.

"*" indicates required fields

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |