Massive, open, online courses, or MOOCs, were a key topic of the higher education discourse during 2012. Discussions of how MOOCs might fundamentally change higher education spread from within the higher education community to mainstream publications. 2012 even saw the development of a MOOC about MOOCs. MOOCs have been a hot topic of discussion because of their potential to reduce the cost of delivering courses, enabling institutions to educate great numbers of students.

While nobody doubts MOOCs will improve access to college-level coursework, a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education led me to question the impact widespread adoption of MOOCs may have on student success, particularly for students from disadvantaged socioeconomic groups.

The suite of services offered by colleges and universities can be thought of as a “bundle” students are required to purchase – when enrolling in college or university, students support and receive numerous services in addition to course content. As highlighted by the University Ventures Fund, MOOCs may contribute to the “unbundling” of services provided by universities, stripping the delivery of course content away from other university functions, such as research, residential life, and student support services. University Ventures Fund and David Stavens, founder of the MOOC Udacity, agree that non-elite institutions will be likely to unbundle services in order to deliver content to students cheaply. As the Chronicle notes, socioeconomically disadvantaged students would likely be more inclined to pursue low-cost, “unbundled,” degrees at non-elite institutions than students able to pay a premium price for a campus-based experience.

Sadly, it is students from disadvantaged backgrounds that are most in need of the complete “bundle” of services currently offered by campus-based colleges and universities. Disadvantaged students benefit greatly from academic and non-academic support resources included in the “bundle” offered by colleges and universities, as these services improve the persistence, and ultimately degree completion, of these students.

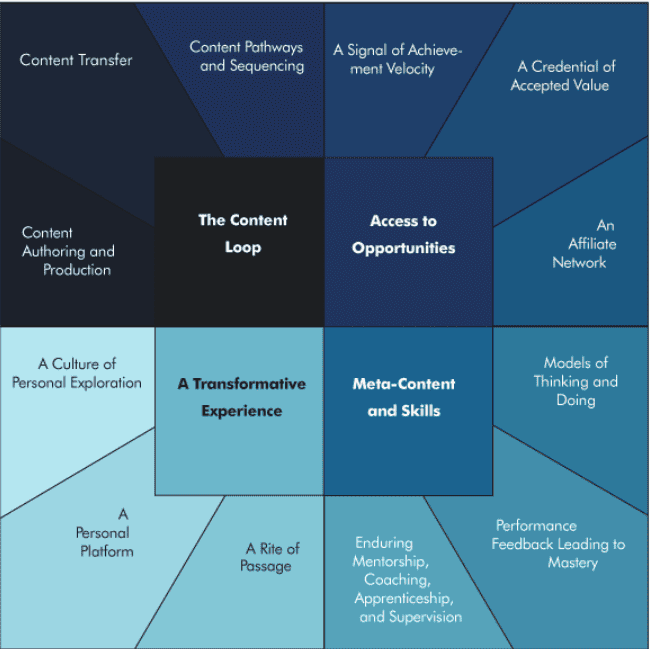

M.P. Staton’s framework for unbundling higher education, which highlights the twelve services comprising most of a college or university’s value proposition to students. Note the services are listed in the order of most easily replaceable by technology (darkest color) to those least easily replaceable by technology (lightest color). Many of the academic and non-academic supports provided by colleges and universities fall within Staton’s meta-content and skills grouping, indicating they are not easily replaceable by technology.

Of course, MOOCs have the potential to improve student outcomes. Studies indicate online learning may be as effective, if not slightly more effective, then classroom-based learning in building student knowledge. Furthermore, MOOCs may improve student persistence and graduation rates by reducing the cost of higher education, and may improve student engagement by increasing the number of students learning from elite professors and benefiting from strong learning communities.

Perhaps the colleges and universities that most effectively utilize MOOCs won’t be those that that do so as a part of a sweeping “unbundling” of their services, but rather, alongside traditional classrooms and student supports. For example, the University of Texas is exploring options to offer highly-demanded courses in both MOOC and traditional formats, limiting instances of students being unable to take over-enrolled courses. San Jose State is examining opportunities to allocate slots in credit-bearing MOOCs to groups that may be attending the university in the future, including high school students and community college students, enabling them to earn credit prior to enrolling in a four-year institution. These thoughtful uses of MOOCs may help reduce the time required to complete a college degree – a major barrier to the success of students from disadvantaged backgrounds – without a reduction in support services.

I am hopeful colleges and universities will leverage MOOCs in creative ways and proceed with caution if deciding to “unbundle” courses from support services. Perhaps efficiency gains resulting from effective uses of MOOCs will improve the ability of colleges and universities to invest more in their support services and reduce the cost of a college degree – a result that would lead to improvements in college access while ensuring students in need of support are able to excel.

Have you seen universities adopting other interesting uses for MOOCs? Do you think an “unbundling” of higher education is inevitable?