2 rattlesnakes. 2 tarantulas. 1 Peregrine Falcon. 1 flash flood. 1 night alone in a canyon wall. 80-foot rappels. Hiking in and around a canyon in southeast Utah with 10 strangers and no one else around for miles and miles.

As of a few months ago, I could check all of these items off of my bucket list, having completed a 10-day Outward Bound "canyoneering" course. As someone who had spent exactly two days camping in my life prior to this adventure (one of which was in my parents' back yard), this was a risk. But life has taught me that with risk comes reward, and I jumped at the chance to experience something pure, primal, and potentially formative. I admit it – I also wanted to turn off my cell phone for 10 days!

But during my days in the wilderness, I realized that there were bigger forces at play, carefully guiding me toward the personal growth that I hoped to attain. So, I'd like to tell you a short story of what I learned the Utah desert, and how those lessons made me think differently about how we should be teaching our youth.

Kurt Hahn and the Educational Philosophy of Outward Bound

Outward Bound is an international nonprofit that takes youth and adults on wilderness expeditions in order to develop leadership and self-awareness through experiencing the outdoors and working in teams. The organization's German-born Jewish founder, Kurt Hahn, was an educator by trade Hahn's public and forceful criticism of Hitler prompted his imprisonment and subsequent emigration to Britain in 1933. While in Britain, Hahn was approached by Lawrence Holt, an owner of a merchant shipping line, whose ships were being torpedoed by German U-Boats in the lead-up to WWII. Holt wanted Hahn's help solving a troubling phenomenon: stranded young sailors, seemingly fit and resilient, died more frequently than stranded old sailors. Holt was quoted as saying "I would rather entrust the lowering of a lifeboat in mid-Atlantic to a sail-trained octogenarian than to a young sea technician who is completely trained in the modern way but has never been sprayed by salt water." Thus, Hahn and Holt concluded that the distinguishing factor between young and old was not technical survival skills, but rather that the older sailors possessed self-reliance, selflessness, and core experiences that could guide them through grueling trials. In other words, it was strong character and internal strength that kept the sailors alive.

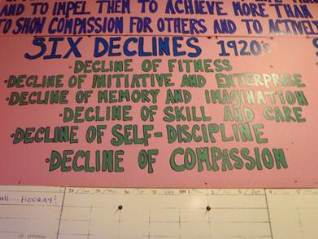

This observation aligned with Hahn's critique of modern society, and compelled Hahn and Holt to found Outward Bound to remedy what Hahn saw as the six declines of modern youth (you can read more about Outward Bound's founding philosophy and Hahn's amazing personal story in the book Outward Bound USA: Crew not Passengers)

- Decline of fitness due to modern methods of locomotion [moving about];

- Decline of initiative and enterprise due to the widespread disease of spectatoritis;

- Decline of memory and imagination due to the confused restlessness of modern life;

- Decline of skill and care due to the weakened tradition of craftsmanship;

- Decline of self-discipline due to the ever-present availability of stimulants and tranquilizers;

- Decline of compassion due to the unseemly haste with which modern life is conducted or as William Temple called “spiritual death.”

Sound familiar? When I learned the story of Outward Bound's founding philosophy, I couldn't help but think that Hahn's observations were prescient; his lament of "spectatoritis" and "spiritual death," and his critique of the "decline of memory" and "decline of skill and care" should ring true to today's educators. There is much to learn from Hahn's observations. Perhaps the ailments of modern youth are not that dissimilar to the ailments of previous eras, and perhaps the cures share traits as well.

For Hahn, the cure was outdoor, experiential education. I can say from my experience – even at the age of 32 – that if one is open to it, outdoor experiential education can be transformative. Testing yourself in the wilderness stares those "six declines" straight in the eye and conquers them one-by-one. Outdoor education forces resiliency through failure, self-knowledge through reflection, and self-belief through teamwork and personal perseverance. Hahn said that Outward Bound "must be less a training for the sea than through the sea, and so benefit all walks of life." For example, in one fell swoop, my learning to use a topographic map exemplifies the small transformations that can come about through experiential education:

After one particularly long day of hiking, instead of resting I took the initiative by asking our instructors to teach me map-reading skills, and even though they were exhausted, they showed compassion by gladly taking the time to teach me. Learning to read a map requires correctly and chart one’s course requires great skill and care – even small errors could cause you to go off course. Although I eventually learned how to read the map, learning proper technique was difficult at first and required self-discipline to try and try again, and memory to make the lessons stick. I never thought that the (seemingly) simple task of map reading would challenge me in so many ways, and that this would rekindle in me the fundamental lessons of craftsmanship, initiative, compassion, discipline, and memory. But after some reflection, I now see that Outward Bound’s educational philosophy deliberately sparked me to re-learn those fundamental life lessons.

What does this mean for how we educate our youth?

As we work to improve student outcomes, I believe we should re-center on the basics of what it is to be a successful adult in a rapidly-changing world: to be self-aware, to be compassionate, and to persevere. One can read about these characteristics in a book or see them in a movie, but until tested in real life, they will not be truly understood and believed. A master's degree in, say, engineering is a great way to qualify for a job, but to succeed in life requires intangibles forged by experience. Outward Bound and programs like it seem to me a fantastic way to bestow these principles on our youth.

What does this practically mean for the education system, and for parents? It means that experiential education intuitively works. Experiential education doesn't have to take place in the wilderness, either. Back in my hometown of Birmingham, Alabama, I was part of a wonderful organization called YouthServe which ran "urban summer service camps." During these week-long residential camps, we took teenagers (half from the suburbs, and half from the inner city) to do various community service activities. Through these experiences, the campers tested themselves, came to believe in themselves and each other, and became leaders before our very eyes. It was as close to magic as I have ever seen. There is nothing like testing one's mettle than hoeing dirt in a community garden in the Alabama sun!

The point is that our youth need experiences that challenge them (albeit in a safe environment) in order to be successful adults. I'm not talking only success in a career. I'm talking about success in life. The greater degree to which we can integrate this philosophy into our instruction, the better.

My questions to this blog's readers are: what examples have you seen of successful experiential education programs? (hint: there are many!). How can experiential education be integrated into the K-12 and post-secondary systems? How have YOU grown through being deliberately challenged? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

I will leave you with two items. 1) A quote by Willi Unsoeld, a legendary Outward Bound instructor who teaches us about the real value of the wilderness. 2) Some photos of Kurt Hahn’s and Outward Bound’s values, taken from the Moab, Utah Outward Bound office.

"Why don't you stay in the wilderness? Because that isn't where it is at; it's back in the city, back in downtown St. Louis, back in Los Angeles. The final test is whether your experience of the sacred in nature enables you to cope more effectively with the problems of people. If it does not enable you to cope more effectively with the problems – and sometimes it doesn't, it sometimes sucks you right out into the wilderness and you stay there the rest of your Life – then when that happens, by my scale of value; it's failed. You go to nature for an experience of the sacred…to re-establish your contact with the core of things, where it's really at, in order to enable you to come back to the world of people and operate more effectively. Seek ye first the kingdom of nature, that the kingdom of people might be realized."

*Thanks to Steve Creech of the Colorado Outward Bound School for the photos and for filling in the details of Outward Bound's history!