Over the past year, FSG has partnered with the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation to explore the critical challenge of eliminating systemic health disparities for patients with serious diseases that require specialty care. These disparities are pervasive and persistent, with disturbing differences between rich and poor, urban and rural, men and women, and others in diagnosis, quality of treatment, and mortality.

As recent studies have shown, the gap in average lifespan between the rich and the poor in the United States has grown over time: for those born in 1950, the top 10 percent of income earners now live 13 years longer than the bottom 10 percent of earners—a gap that is twice as large as it was for those born 30 years earlier, and one that equates to 15 percent of the average lifespan in this country.

Our approach to health care in the United States contributes to these disparities. While the health care sector has developed remarkable advances in medical treatment, the structure of our delivery system consistently limits access to these same advances. For example, nearly half of all deaths in the United States are caused by heart disease and cancer, both of which require specialty care. But too many low-income people struggle to find a specialist who will see them and too many rural patients are forced to travel great distances to access specialty care. For those who are able to gain access, high out-of-pocket costs, from co-pays to prescription medication, put needed care out of reach for many.

In addition, specialty fields have historically treated illness as a singular problem. Focusing resources on treatment and cure leaves fewer resources for other contributing factors and elements of care, such as patient understanding and trust, psychosocial support, and patient access to basic needs such as housing and food. And lastly, the health care delivery system has not consistently helped health care providers assess how their own implicit biases and unconscious attitudes toward certain groups of patients might compound the challenges that patients face.

Together, these dynamics have resulted in substantial disparities in health outcomes for those experiencing serious diseases, along dimensions of race and ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation, English proficiency, geography, and socio-economic status. The 5-year survival rate for lung cancer, for example, is 20 percent lower for black patients than for white patients. People with lower socio-economic status have a 50 percent greater risk of developing heart disease than those with higher incomes and more education. The same pattern holds for HIV—despite accounting for only 12 percent of the U.S. population, black men and women account for 45 percent of new HIV diagnoses but are less likely to be retained in treatment.

The picture, however, is not entirely bleak. A major benefit of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the growing focus on health care quality and outcomes and a greater understanding of the link between eliminating disparities and controlling health systems costs and improving quality. As a result, there is tremendous energy across the health care system—not just for developing the next “blockbuster” drug, but also for creating new models of care to improve outcomes and reduce costs, new methods of data collection and analysis to identify and address disparities, and new partnership models to better reach and support populations that experience the deepest inequity.

What is needed now is for actors across the health system, including public and private insurers, health care providers and provider organizations, community organizations, and policy-makers at the federal and state levels to work together to incubate, scale, and sustain these solutions.

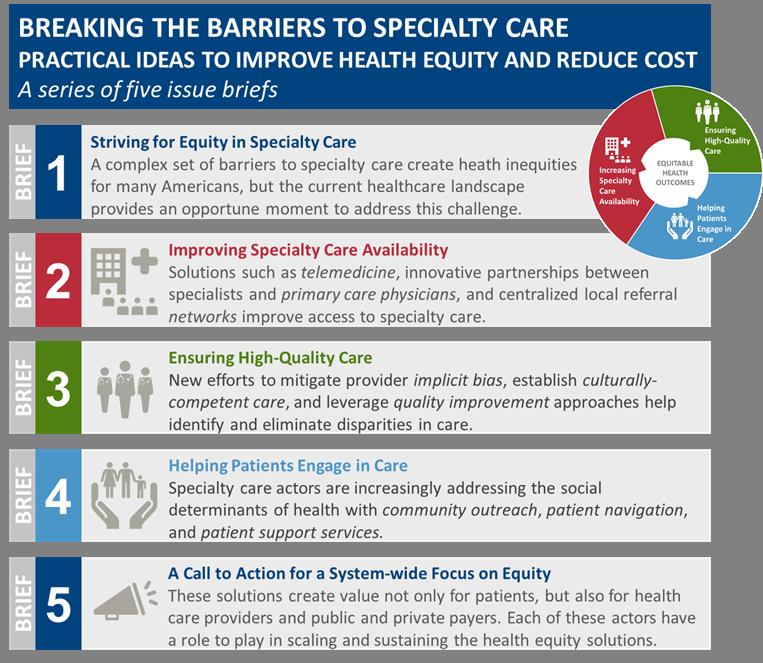

To support the field in driving this change, FSG and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation have developed a series of 5 issue briefs aimed to serve as a resource for those seeking to improve equity across the health care sector. Included in the briefs are data and analysis on health disparities and the barriers that minority and medically underserved populations face when seeking specialty care, case studies of effective solutions, examples of how policymakers, payers, and private funders are supporting change, and recommendations for system-wide change.

The publication of these briefs represents the culmination of months of research and over 70 conversations with health care practitioners and equity leaders. In the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing an ongoing series of stories and interviews that highlight some of the incredible work that is happening today to reduce inequity and improve health outcomes for all. We look forward to being part of this important dialogue.